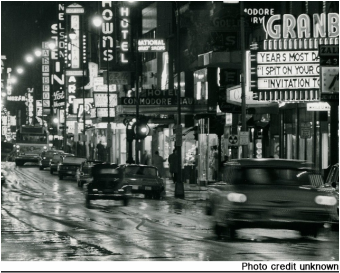

By the mid-sixties, the first-run movie theaters of downtown Norfolk, Virginia, the formerly seedy seaport town from where I hail, were well beyond their glory days. Fear of crime and the convenience offered by the new suburban shopping centers had taken their toll on the crowds of consumers that had once flocked to the stores and venues along Granby Street.

Theaters that hadn't switched to showing softcore porn to snag sailors on shore leave were juggling second-run Hollywood features with low-budget exploitation fare. The venerable Granby Theater abandoned first-run fare in favor of Succubus (1968) and The Horrors of Spider Island (1965). The Byrd, a decrepit fleapit of a theater where The Giant Behemoth (1959) had terrorized me as a six-year-old, hosted Torture Dungeon (1970) and other no-budget oddities before shutting its doors for good in late 1970. The Norva, now a concert hall, was the site of the local premiere of the Italian "mondo" film that had been retitled for U.S. audiences as Ecco (1965).

Theaters that hadn't switched to showing softcore porn to snag sailors on shore leave were juggling second-run Hollywood features with low-budget exploitation fare. The venerable Granby Theater abandoned first-run fare in favor of Succubus (1968) and The Horrors of Spider Island (1965). The Byrd, a decrepit fleapit of a theater where The Giant Behemoth (1959) had terrorized me as a six-year-old, hosted Torture Dungeon (1970) and other no-budget oddities before shutting its doors for good in late 1970. The Norva, now a concert hall, was the site of the local premiere of the Italian "mondo" film that had been retitled for U.S. audiences as Ecco (1965).

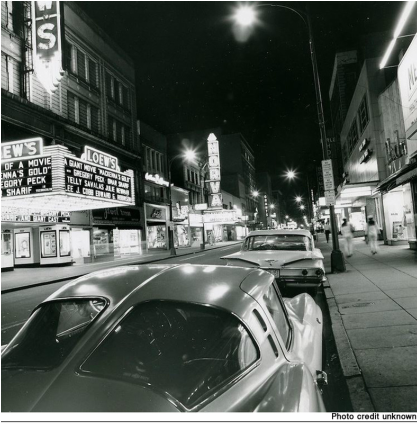

The posh 2,100 seat Loews Theater ("Dixie's Million Dollar Dandy"), which had opened to great fanfare in 1926 with the silent comedy Beverly of Graustark starring William Randolph Hearst's own rosebud, Marion Davies, was likely to follow the first-run engagement of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) with the re-release of the double-billed Blood Feast and Two Thousand Maniacs.

It was at the Loews where I first saw Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969) and Straw Dogs (1971), and endured such grindhouse legends as Mark Of The Devil (1970), The Last House On The Left (1972), and Twitch Of The Death Nerve (1972). It's also where I stumbled across Nelson Lyon's The Telephone Book (1971), a surreal satire so obscure it was once believed to be lost, or to have never existed at all.

It was at the Loews where I first saw Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969) and Straw Dogs (1971), and endured such grindhouse legends as Mark Of The Devil (1970), The Last House On The Left (1972), and Twitch Of The Death Nerve (1972). It's also where I stumbled across Nelson Lyon's The Telephone Book (1971), a surreal satire so obscure it was once believed to be lost, or to have never existed at all.

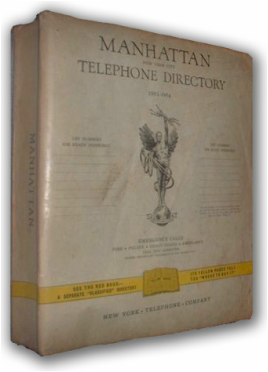

Because it fetishizes outdated technology and depicts behavior then considered transgressive that now seems quaint, the black and white The Telephone Book can be appreciated as a time capsule from a bygone era. Set in New York City, ground zero for cool until 1993 when Rudy Giuliani reshaped it into an urban Disneyland for midwestern tourists, The Telephone Book was inspired by the old saw about a movie director challenged to make a film based on the most impossible of sources: the Manhattan telephone directory. Writer/director Lyon, an ad man by trade, turned this seemingly unfilmable premise into a tale of telephone scatologia that amply demonstrates why his friends called him "Dr. Smut."

Blonde, helium-voiced Alice (Sarah Kennedy) struggles with ennui in her sparsely furnished - only a bed! - high-rise until the day she receives what is apparently the granddaddy of obscene telephone calls. Aroused by the creativity of the sonorously-voiced reprobate, she insists on knowing his name. It's John Smith, he tells her, and he's in the phone book. So begins Sarah's quest to locate her aural exciter by calling every John Smith in the Manhattan phone book until the right one answers.

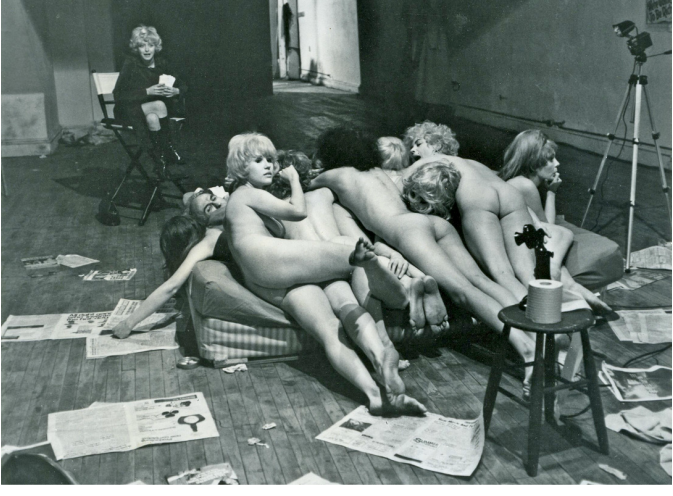

As luck would have it, every New Yorker she encounters, whether named John Smith or not, is either a kook or an outright pervert, as in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (although the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences somehow failed to recognize Lyon’s effort). This screwball scenario is padded to feature length through the seemingly random insertion of interviews with actors portraying reformed obscene callers, and by stock footage used to similar effect in Michael Sarne’s regrettable adaptation of Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge from the previous year.

Blonde, helium-voiced Alice (Sarah Kennedy) struggles with ennui in her sparsely furnished - only a bed! - high-rise until the day she receives what is apparently the granddaddy of obscene telephone calls. Aroused by the creativity of the sonorously-voiced reprobate, she insists on knowing his name. It's John Smith, he tells her, and he's in the phone book. So begins Sarah's quest to locate her aural exciter by calling every John Smith in the Manhattan phone book until the right one answers.

As luck would have it, every New Yorker she encounters, whether named John Smith or not, is either a kook or an outright pervert, as in John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (although the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences somehow failed to recognize Lyon’s effort). This screwball scenario is padded to feature length through the seemingly random insertion of interviews with actors portraying reformed obscene callers, and by stock footage used to similar effect in Michael Sarne’s regrettable adaptation of Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge from the previous year.

For older viewers, the most intriguing facet of The Telephone Book might be its offbeat cast. Those who remember the television series The Fugitive will recognize Barry Morse (Lt. Philip Gerard, the nemesis of Richard Kimble) as Har Poon, “the world’s greatest stag film actor.” Two of Andy Warhol’s “superstars,” Ondine and Ultra Violet, are also on hand, as is groupie/go-go dancer Geri Miller from the Warhol-produced Flesh (1968) and Trash (1970). In his commentary on the Vinegar Syndrome dual-format release of The Telephone Book, producer Merwin Bloch reveals that Warhol himself was filmed for a segment that was later excised, to Bloch’s eternal regret, to tighten the pacing. Future porn star Marlene Willoughby makes an appearance, and rubber-faced character actor Roger C. Carmel (Harry Mudd from Star Trek) gives a standout comic performance as a leering subway flasher.

Most unexpectedly, the late Jill Clayburgh, star of Paul Mazursky's An Unmarried Woman (1978), portrays Alice's unnamed friend, a Manhattan caricature always shown in bed wearing an eye mask. (Bloch notes in his commentary that Clayburgh was offered the lead role but declined due to the requisite nudity.) The most inspired casting, however, is soap opera star Norman Rose as Mr. Smith, the obscene caller. Rose’s smooth baritone, dubbed “the voice of God” by his contemporaries, is immediately recognizable from his many television commercials (he was Juan Valdez for the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Columbia).

The eventual mask-to-face meeting of Mr. Smith and Alice is a perverse yet oddly charming echo of classic Hollywood romances. It’s also the apogee of a hipster’s love of antiquity as reflected in the vintage movie posters adorning Har Poon’s bare studio and the scratchy recording of 1930’s torch singer Helen Morgan crooning “Something to Remember You By” that accompanies the opening credits. At its most inspired, Lyon’s script forces the viewer to imagine, rather than actually hear, the ne plus ultra of Mr. Smith’s obscenities. His finely-wrought filth is represented in a climactic scene through a color cartoon sequence by Leonard Glasser that, though crudely inked and animated, more accurately represents the style and sensibility of underground “comix" than anything Ralph Bakshi ever dared.

Millennials will probably respond with bemusement to a film set in a world where people searched for phone numbers in a book so thick that it was often used as a booster seat for children, where the identity of a person on the other line was not betrayed by caller ID, and the sight of two adjacent phone booths didn’t seem at all unusual. It was a moment in time between a more circumscribed era when you might lose your day job for appearing in a nudie film (a la Audrey Campbell) and the anything-goes world of hardcore porn. Following the X-rated The Telephone Book, her film debut, Sarah Kennedy joined the cast of Dan Rowan and Dick Martin’s waning comedy series Laugh-In to claim the “giggly blonde” role after the departure of Goldie Hawn.

Nelson Lyon was subsequently hired as a writer for Saturday Night Live, where he befriended a chubby comic who soon became the program’s most popular performer. Lyon's involvement in the cocaine and heroin-fueled orgy that killed his portly pal, John Belushi, on March 5, 1982, resulted in him being blacklisted by the film and television industry. He died in 2012, the same year that Norfolk's evolving Loew's Theater, now owned and operated by a local community college, commemorated its rich cinematic history - and the law of diminishing returns - by screening Michel Hazanavicius' genteel silent film The Artist (2012). As with Manhattan, it's a different town now.

Nelson Lyon was subsequently hired as a writer for Saturday Night Live, where he befriended a chubby comic who soon became the program’s most popular performer. Lyon's involvement in the cocaine and heroin-fueled orgy that killed his portly pal, John Belushi, on March 5, 1982, resulted in him being blacklisted by the film and television industry. He died in 2012, the same year that Norfolk's evolving Loew's Theater, now owned and operated by a local community college, commemorated its rich cinematic history - and the law of diminishing returns - by screening Michel Hazanavicius' genteel silent film The Artist (2012). As with Manhattan, it's a different town now.

Also reviewed for this edition of ecco: El Vampiro Negro (1953), It Follows (2015), and Return From the Ashes (1965). Added to the archive is Freeway (1996).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed