With over 270 feature films - and sixteen programs of featurettes and shorts - stuffed into its eleven days and nights, the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF for short) can chew up and spit out the most hardy of cinephiles without a ruffle of its ruby red carpet. Far be it from me, however, to take the tack of the dyspeptic, put-upon cineaste who wheezes about how s/he endured this never-ending parade of poseurs and their godawful festival films in order to reassure you, a movie lover in Argonne, Wisconsin, that your HBO account and Netflix subscription are all you need.

No, TIFF 2014 was primarily a delight, offering a smorgasbord of digital and celluloid delicacies along with its inevitable non-edibles. Further, TIFF and similar festivals may be the only option for seeing certain works theatrically, even in major metropolitan areas, now that the distribution of non-mainstream films has been cherry-picked for commercial potential by chains such as Landmark and Angelika or left at the mercy of budget-squeezed college and museum programmers. One admittedly specific example: Margaret Honda's transcendent Spectrum Reverse Spectrum, made without a camera on 70mm film, exists in only two prints, one of which was screened at TIFF 2014. There will be no digitized version or additional prints per the filmmaker, so good luck seeing that one no matter where you live.

Opening TIFF 2014 was The Judge from director David Dobkin (Wedding Crashers), a courtroom drama starring Robert Downey, Jr. and Robert Duvall. You can go here if you're interested; I wasn't. My entry to the fest was Olivier Assayas' The Clouds of Sils Maria, which recalls in its skillful juxtapositions of "being" and "acting" the filmmaker's Louis Feuillade tribute, Irma Vep (1996). The shaky bond between a middle-aged actress (Juliette Binoche, late of Godzilla) and her tech-savvy young assistant (Kristen Stewart) mirrors the characters of a Chekhovian play they testily rehearse about a calculating neophyte in the business world who cruelly usurps the role of her elder supervisor and lover. Binoche's character once starred as the younger woman but must now portray the victim opposite an up-and-coming enfant terrible (Chloë Grace Moretz). Assayas has claimed that he wrote the film for Binoche, whose stunning performance rivals her work in Bruno Dumont's Camille Claudel 1915 (2013). Binoche and Stewart's complex characterizations set the stage for a festival filled with notable performances by women, a welcome rejoinder to the two-dimensional female cyphers of contemporary popular cinema.

No, TIFF 2014 was primarily a delight, offering a smorgasbord of digital and celluloid delicacies along with its inevitable non-edibles. Further, TIFF and similar festivals may be the only option for seeing certain works theatrically, even in major metropolitan areas, now that the distribution of non-mainstream films has been cherry-picked for commercial potential by chains such as Landmark and Angelika or left at the mercy of budget-squeezed college and museum programmers. One admittedly specific example: Margaret Honda's transcendent Spectrum Reverse Spectrum, made without a camera on 70mm film, exists in only two prints, one of which was screened at TIFF 2014. There will be no digitized version or additional prints per the filmmaker, so good luck seeing that one no matter where you live.

Opening TIFF 2014 was The Judge from director David Dobkin (Wedding Crashers), a courtroom drama starring Robert Downey, Jr. and Robert Duvall. You can go here if you're interested; I wasn't. My entry to the fest was Olivier Assayas' The Clouds of Sils Maria, which recalls in its skillful juxtapositions of "being" and "acting" the filmmaker's Louis Feuillade tribute, Irma Vep (1996). The shaky bond between a middle-aged actress (Juliette Binoche, late of Godzilla) and her tech-savvy young assistant (Kristen Stewart) mirrors the characters of a Chekhovian play they testily rehearse about a calculating neophyte in the business world who cruelly usurps the role of her elder supervisor and lover. Binoche's character once starred as the younger woman but must now portray the victim opposite an up-and-coming enfant terrible (Chloë Grace Moretz). Assayas has claimed that he wrote the film for Binoche, whose stunning performance rivals her work in Bruno Dumont's Camille Claudel 1915 (2013). Binoche and Stewart's complex characterizations set the stage for a festival filled with notable performances by women, a welcome rejoinder to the two-dimensional female cyphers of contemporary popular cinema.

Standout performances by German actress Nina Hoss as the disfigured survivor of a Nazi concentration camp and Ronald Zehrfeld as her scheming husband highlight Christian Petzold's neo-noir Phoenix. At times visually evocative of Hitchcock, Fassbinder, and Franju, the latter in a spooky scene set in a medical clinic, Phoenix was one of TIFF 2014's most tautly crafted thrillers. Written by Petzold with the late filmmaker and theorist Harun Farocki, the melodramatic script is (very) loosely based on the lurid 1961 novel Le retour des cendres by French author Hubert Monteilhet, which was also the source of J. Lee Thompson's near-forgotten Return From The Ashes (1965). Phoenix transcends these pulpy roots much as its central character must ultimately learn to reject her former life to be reborn like the mythological bird that informs the film's title. It's also capped off with one of the most satisfying conclusions of recent note, earning shouts and applause from the TIFF audience. Phoenix continues Petzold's fascination with his country's painful past as demonstrated in his international breakthrough Barbara (2012), a cold war drama which also featured both Hoss and Zehrfeld in compelling lead performances. In fact, Petzold has been scrutinizing the conscience of postwar Germany since his feature film debut The State I Am In (2000). Phoenix further cements his reputation as the leading light of the Berlin School.

National Gallery is master documentarian Fred Wiseman's latest addition to his lifelong task of capturing the processes behind various institutions, a goal that stretches back to his first feature, the long-banned Titicut Follies (1967). Nearly three hours in length, National Gallery is Wiseman's behind-the-scenes peek at the National Gallery of London. Though there is the expected footage of board meetings and other administrative goings-on, much of the film's runtime consists of a gallery viewer's look at exhibits of paintings by the Old Masters, the collection's specialty. Wiseman's shooting schedule coincided with special exhibits of paintings by Leonardo Da Vinci, Titian, and J.M.W. Turner, all of which are viewed along with their viewers. In every Wiseman film we learn how institutions function, and National Gallery provides an education in the painstaking processes behind the restoration of delicate oil paintings. We also learn about the works themselves through the words of museum docents tracked by Wiseman's camera through the galleries. As a Wiseman film, however, National Gallery is less compelling than recent projects such as Boxing Gym (2010), perhaps because the level of human interest is overwhelmed by the worshipful attention given the artwork. In one clip, the museum's director stresses to a subordinate how he is unwilling to allow any organization to project images onto the building's facade for fear that such an act would imply endorsement. Later, a group of protesters hang a banner condemning the petroleum industry over the museum grand entrance, effectively realizing the director's fears. The absence of an official's feedback on this act seems like a forfeited opportunity. Wiseman's Q&A following the film proved to be more entertaining than the feature. At age 84 he sees no need to suffer fools gladly, and offered barbed responses to the audience's typically inane questions. When asked about his next project, Wiseman replied that he was working on a musical based on Titicut Follies featuring himself as lead performer.

On the other end of the age spectrum, nineteen-year-old Arielle Holmes portrays a barely fictionalized version of herself in Benny and Joshua Safdie's searing Heaven Knows What, a mashup of fiction and cinema verité about young NYC heroin addicts. The mainlining is real, and occasionally in public places, in this ode to love and dependence filmed on location in vacant lots and fast-food joints. Based on Holmes' unpublished autobiographical novel "Mad Love in New York City," Heaven Knows What offers an unflinching close-up of life on the street as portrayed by the author, her junkie friends, and a smattering of pros such as Brooklyn rapper Necro. In the squalor of addiction, homelessness, and desperation, the Safdies find stark beauty in life lived on the edge. They're aided by DoP Sean Price Williams, whose compositions mercifully refrain from the shaky handheld camera that serves as indie shorthand for "real life." The incendiary script, adapted by the Safdies and filmmaker Ronald Bronstein (2007's Frownland), revolves around the destructive relationship between teen addict Harley (Holmes) and Ilya (Caleb Landry Jones), the unloving object of her obsessive love and the dark angel who first introduced her to heroin. The emotionally aloof Ilya is both the totem of Harley's amour fou and an ambulatory metaphor for the one-sided love affair that is drug dependency. At times reminiscent of smack forbears Midnight Cowboy and Panic in Needle Park, the low-budget, back-alley aesthetic is within spitting distance of the teen shockers of Larry Clark and Harmony Korine.

Another type of obsessive love is the subject of Peter Strickland's bizarre The Duke of Burgundy, which probes the individual sacrifice inherent in maintaining a monogamous relationship. That the liaison he depicts is Penthouse Forum kinky gives Strickland room to ruminate about sexual power dynamics while eliciting successive waves of recognition and nervous laughter from his audience. Following a clever title sequence designed to resemble the credits of an arty seventies' softcore porn film, The Duke of Burgundy introduces matriarchal Cynthia (Sidse Babett Knudsen), an affluent lepidopterist whose collection of pinned and preserved subjects provides the film with its title (FYI: it's a sub-family of butterfly). When not reading or writing about insects, Cynthia inflicts on her young maid Evelyn (Chiara D'Anna) punishments of an increasingly severe sexual nature in return for the slightest infraction. But all is not as it initially seems in the penis-free world of The Duke of Burgundy, and therein resides the rub. Writer-director Strickland furthers his interest in using sound to vividly conjure unseen actions as in his previous film, Berberian Sound Studio (2012), particularly with scenes in which descriptive noises involving a specific sadomasochistic act are heard behind a bathroom door. But despite its old-school kinkiness, the film is never as explicit as its subject suggests. During a Q&A after the screening, Strickland admitted that he had initially planned to remake Jesús Franco's La comtesse perverse (1974), but realized early in planning that one version was enough (though Franco alum Monica Swinn does turn up in a minor role). He subsequently presented a CD featuring field recordings of cricket chirps to one lucky audience member, and confessed that he hoped that the film's title would lure unsuspecting viewers expecting a BBC-type historical drama. They, too, may have found the film clever, alluring, and unexpectedly poignant, providing their willingness to immerse themselves in a world in which one character's idea for the perfect birthday gift is a "human toilet."

Turkish filmmaker Nuri Bilge Ceylan's 196-minute Winter Sleep also explores, at the director's signature deliberate pace, the hidden recesses of a rocky relationship. The winner of the Palme d'or at this year's Cannes festival, the unusually verbose (for Ceylan) Winter Sleep charts several days in the troubled marriage of Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), a former Shakespearean actor turned landlord and proprietor of a hotel catering to tourists, and Nihal (Melisa Sozen), his impetuous younger wife. The wealthiest man in town, Aydin's comfortable life is shown in sharp relief to the deprivations suffered by his neighbors, particularly one hardscrabble family of renters. His oblivious self-regard has also alienated his wife and his divorced sister (Demet Akbag), whose presence in the household sparks bitter recriminations. Unlike his previous feature, the Dostoevskian "whydunit" Once Upon A Time In Anatolia, Ceylan's new film charts the more mundane human transgressions of greed, pride, and the smug conviction of intellectual superiority. The raw human interactions of Winter Sleep become the mirror that just might reveal to Aydin the true nature of his own flawed character. Gökhan Tiryaki, Ceylan's cinematographer since his fourth feature Climates (2006), employs Rembrandt-worthy lighting and intimate, close-up photography to expose the percolating emotions betrayed by the human face. A switch from his award-winning work for the painterly landscapes of Anatolia, it is no less beautiful. Ceylan's cast is equally up to the challenge. Haluk Bilginer, a veteran of British theatre, excels as a proud man blind to the needs of those around him. Also of note are Melisa Sozen as Aydin's belittled wife and Nejat Isler as a drunken tenant whose crumpled pride leads to cynical defiance. Would-be viewers should not be put off by the film's lengthy runtime, for Ceylan doesn't squander a minute.

Shakespeare is the primary inspiration for Matías Piñeiro's airy, avant-garde comedy La Princesa de Francia, though the Argentine filmmaker is less interested in hewing to his source, the Bard's Love's Labour's Lost, than he is in having fun in a modern setting with the play's complex romantic entanglements. Departing from the strategy of his short film Rosalinda (2011) and previous feature Viola (2012), Piñeiro's latest revolves not around a female character from Shakespeare's comedies but a handsome young man. Recently returned to Buenos Aires from an extended stay in Mexico, former theatre director Victor (Julián Larquier Tallarini) begins work on a hip hop-inspired radio production of Love's Labour's Lost, intent on avoiding the romantic distractions that had apparently derailed his previous efforts. But by enlisting the aid of his former theater troupe, young actresses with whom he has either already has amorous connections, including his ex-girlfriend, or enticing newcomers, Victor's efforts seem doomed from the start. This simple narrative concept, however, serves as only a framework for Piñeiro's complex roundelay of thwarted assignations and unfaithful lovers. At one point, taking the theme of romantic confusion beyond Elizabethan recognition, Piñeiro re-stages the same scene thrice, with the same character acting against a different partner, with different outcomes, in a rondo of seductive scheming. An inscribed museum postcard slipped into a bound copy of the play changes hands until its discovery at the conclusion, a nod to the mis-delivered letters of Shakespeare's original. Piñeiro has stated that he grew familiar with Shakespeare not as works of theatre but as literature, and the attentive concentration on the sound of language, specifically the cadence of Elizabethan dialogue recited in Spanish, is one of the highlights of La Princesa de Francia. There are no other films similar to those by Matías Piñeiro, and La Princesa de Francia is unlike anything else you will see this year. Given its complexity, Piñeiro's most challenging film to date bears repeated viewings, but the playfulness and intelligence behind its conception are readily apparent. Be sure to stay for the charming post-credits postscript, the cries of an infant that was in utero during filming.

You'd be better off NOT staying for the contrived conclusion of Ruben Östlund's Force Majeure, an unsatisfying follow-up to the Swedish filmmaker's disturbing Play (2011). The winner of this year's Un Certain Regard Jury Prize at Cannes, Force Majeure eschews the hyper-realism of the previous film for a broadly satirical jab at traditional sex roles. When an induced avalanche threatens to snowball out of control at a Swiss ski resort, a vacationing businessman (Johannes Bah Kuhnke) deserts his wife and children in a panic. His stunned spouse (Lisa Loven Kongsli) is less perturbed by this demonstration of cowardice than his steadfast denial that he ran away, leading to prolonged confrontations that spill over into the relationship of another vacationing couple. But what is at first a squirm-inducing look into the messy results of a craven abandonment of the traditional male role as protector degenerates into silliness, as Östlund gives us his shamed vacationer crouched and blubbering uncontrollably in the hotel hallway. A last-minute stab at sexual equivalency also strikes a false note, as if the filmmaker were attempting to erase his initial Etch-A-Sketch of a premise. It's worth noting that the most courageous individual in Force Majeure turns out to be a minor character who has chosen to live outside the boundaries of the traditional nuclear family, but an intriguing suggestion in the margins is not enough to salvage this curiously non-committal work.

The Wavelengths series of experimental films curated by programmer Andréa Picard provided numerous festival highlights. Antoinette Zwirchmayr's 35mm The pimp and his trophies is a bold, dispassionately narrated recollection of the filmmaker's childhood layered over oddly staged tableux and family photographs of the mirrored walls and upholstered platforms of her grandfather's business establishment. The disclosure that granddad was the most well-known brothel keeper in Salzburg introduces a startling contrast between Zwirchmayr's matter-of-fact delivery, which parallels the casual acceptance of his illicit profession by her family, and her need as an adult to come to terms with its implications. Many of the photographs are viewed bisected by a small mirror, a key emblem in this complex work.

Blake Williams' Red Capriccio recycles YouTube video of a Chevy Caprice police car intercut with crumbling urban architectural structures, all filtered through color filters with near-stroboscopic impact. Williams has said that his film's imagery and juxtapositions were inspired by Capriccio painting and symphonic composition, hence the title's descriptive pun. Viewers are instructed to wear 3D glasses; however, the effect is not one of heightened depth perception but of pulsing, color-saturated intensity.

Blake Williams' Red Capriccio recycles YouTube video of a Chevy Caprice police car intercut with crumbling urban architectural structures, all filtered through color filters with near-stroboscopic impact. Williams has said that his film's imagery and juxtapositions were inspired by Capriccio painting and symphonic composition, hence the title's descriptive pun. Viewers are instructed to wear 3D glasses; however, the effect is not one of heightened depth perception but of pulsing, color-saturated intensity.

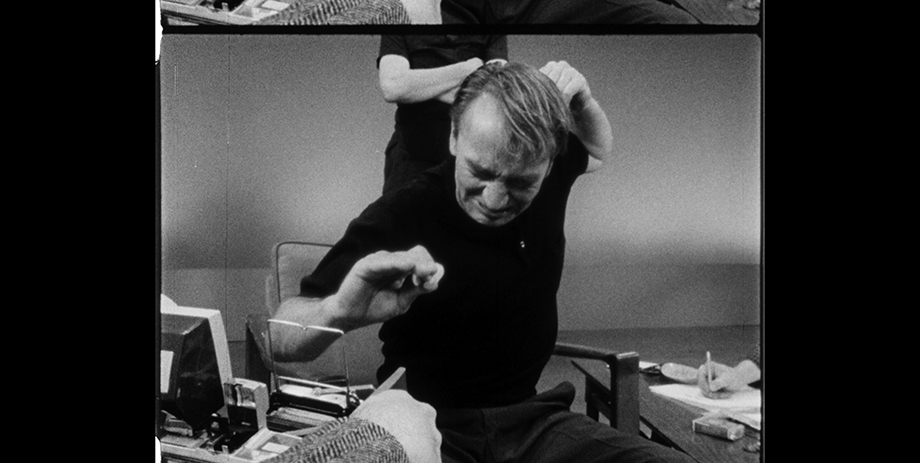

Detour de Force profiles the sixties' exploits of Theodore "Ted" Serios, a former Chicago bellhop who claimed the ability to project images from his brain into a Polaroid camera, resulting in instant photographs of his thoughts. Rebecca Baron's cryptic but frequently hilarious film consists of vintage 16mm footage of Serios and his champion, psychiatrist Jule Eisenbud, as they demonstrate what Serios dubbed "thoughtography" to news cameras and researchers. Audio from tape recordings of Serios, who was frequently intoxicated and belligerent during his sessions, complements the archival images of what was either an unexplainable feat of mental projection or a trick worthy of Penn and Teller.

Johann Lurf's Twelve Told Tales chops up 35mm logos for major Hollywood studios into a flashing, frenetic, retina-searing assault on the senses that pulses through the viewer's cranium like dopamine. That Lurf's eye for editing has produced a more pleasurable cinematic experience than anything likely to follow those logos is emblematic of both the sad predictability of contemporary mainstream cinema and the estimable offerings featured in the Wavelengths program. If only someone would take a splicer to the three years of fashion porn bumper ads for TIFF sponsor l'Oréal ("because you're worth it")!

This is the first of three parts of ecco film and video's coverage of the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival. Next installment: The Goddess, Pasolini, Jauja, and more!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed