About ecco film and video

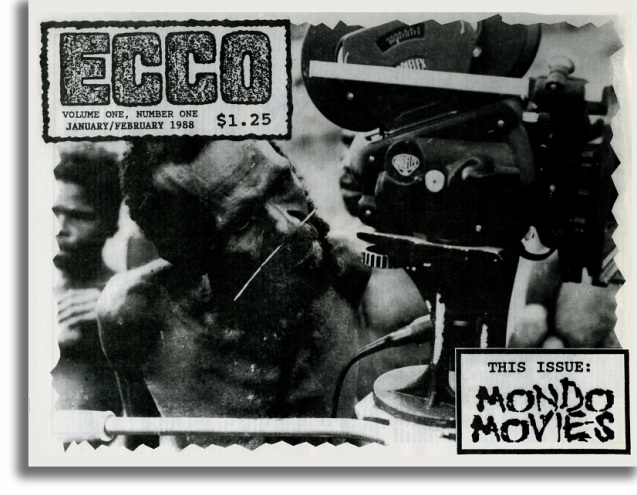

ecco film and video is a continuation of the print-based publication ecco, the world of bizarre video, which first appeared in January 1988. Twenty-one issues followed until it finally sputtered out in 1997. The goal of the original ecco was to document the initial wave of horror and (s)exploitation films on home video, some of which were already familiar to me through many hours spent during my teenage years at the faded downtown movie palaces and drive-in theaters of Norfolk, Virginia, where I took in such fevered fare as "The Horrors of Spider Island," "The Undertaker and His Pals," "The Mighty Gorga," and "The Minx." The demise of drive-ins and "grindhouse" theaters, victims of a consumptive real estate market and urban redevelopment, was superseded by the rise of home video and the availability of cheap "content." Old drive-in and grindhouse fare was being brushed off for home video, often with misleading box artwork or changed titles. It was the latest incarnation of the "ballyhoo" approach to marketing low-budget exploitation films that I had observed for years in newspapers and on marquees.

After I moved to Washington, DC in the mid-seventies, the Motion Picture Reading Room of the Library of Congress provided access to a collection of books, magazines, and journals, as well as film prints, that would have been difficult to top in the pre-Internet era. In the specialty and academic books and journals of the Library of Congress, I discovered articles about the films I'd seen at dusk-to-dawn shows - and others known to me only by title.

In the mid-eighties appeared a local business, The Video Vault of Virginia, that specialized in "cult" movie rentals and promised in their advertising to offer the "guaranteed worst films in town." One visit to their shop and I was soon reconnecting with old drive-in friends such as "Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!" A lucky visit to Philadelphia resulted in the discovery of a dusty little movie memorabilia store with scores of posters, stills, and pressbooks for the films I loved, and all were priced fire-sale cheap.

This confluence of opportunities was too exciting to ignore. ecco, then, grew out of my curiosity about the films I had seen; and new discoveries, some of which had been only titles I'd read in the pages of reference books. The books, magazines, and periodicals available in the Motion Picture Reading Room provided a great opportunity to learn more about films that had been left out of mainstream film studies. Why not share the information?

In the mid-eighties appeared a local business, The Video Vault of Virginia, that specialized in "cult" movie rentals and promised in their advertising to offer the "guaranteed worst films in town." One visit to their shop and I was soon reconnecting with old drive-in friends such as "Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!" A lucky visit to Philadelphia resulted in the discovery of a dusty little movie memorabilia store with scores of posters, stills, and pressbooks for the films I loved, and all were priced fire-sale cheap.

This confluence of opportunities was too exciting to ignore. ecco, then, grew out of my curiosity about the films I had seen; and new discoveries, some of which had been only titles I'd read in the pages of reference books. The books, magazines, and periodicals available in the Motion Picture Reading Room provided a great opportunity to learn more about films that had been left out of mainstream film studies. Why not share the information?

The name and title design of ecco is taken from the Italian pseudo-documentary World by Night 3, recut and retitled ecco for its U.S. release. This is a film I watched in awe when it played theatrically in 1964, and which sparked my developing fascination with the carnivalesque side of human endeavors. Though the title lettering was stenciled for my first couple of issues, I eventually adopted the film's logo. There are stories about how the logo was created, and this photo of a gas station sign in the southeast U.S. offers further speculation. The Italian word "ecco" translates loosely as the phrase "here it is," which seemed á propos for giving a second chance to films once thought buried beneath parking lots, chain pharmacies, and other sad grave sites of regional drive-ins and grindhouses. It's also not a bad name for a gas station.

ecco film and video will continue the goal of championing neglected films along with covering current and vintage theatrical and video releases. So why the title change? "The world of bizarre video," while provocative-sounding, helped pigeonhole the publication into an almost exclusive focus on horror and sexploitation films. This new version is friendly to non-genre and theatrical releases, freeing its writer from his former, admittedly self-imposed restrictions.

About Charles Kilgore

A fanatic for unpopular cinema since 1959, I published ecco, the world of bizarre video, from January 1988 through May 1997 with the help of several gifted writers. In addition to ecco, my sordid scribblings have been published in Psychotronic Video, Filmfax, Slaughterhouse, Uncut Funk, and others.

For their friendship, help and/or inspiration, I thank the following people, living and deceased: Stephen R. Bissette, Audrey Campbell, Harold Clarke, Eileen Flynn, David F. Friedman, Doug Hobart, H.G. Lewis, Tim and Donna Lucas, Jim and Jane McCabe, David Mills, Jim Murray, Jim Ridenour, Bill Rogers, Dominic Salemi, C. Davis Smith, Jim Tanner, and Mike Vraney and Lisa Petrucci.

- Charles Kilgore

For their friendship, help and/or inspiration, I thank the following people, living and deceased: Stephen R. Bissette, Audrey Campbell, Harold Clarke, Eileen Flynn, David F. Friedman, Doug Hobart, H.G. Lewis, Tim and Donna Lucas, Jim and Jane McCabe, David Mills, Jim Murray, Jim Ridenour, Bill Rogers, Dominic Salemi, C. Davis Smith, Jim Tanner, and Mike Vraney and Lisa Petrucci.

- Charles Kilgore