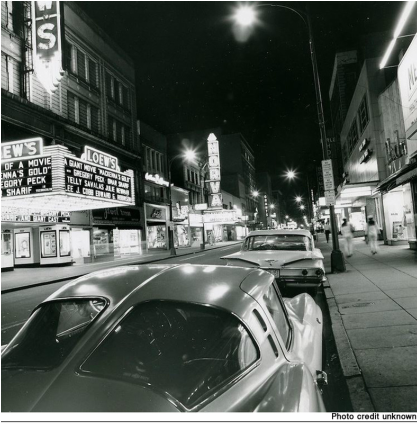

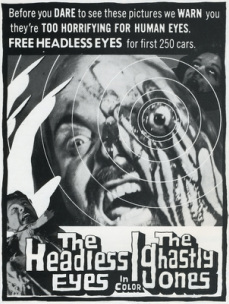

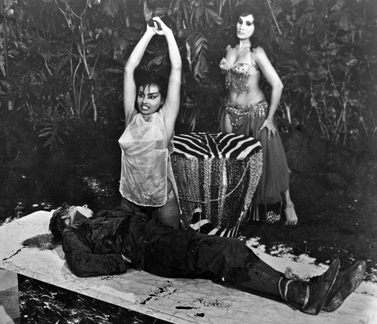

As a teenager, my playground was downtown Norfolk, Virginia. On Saturdays - weekdays if I'd skipped school - I'd catch the downtown bus to see such films as The Honeymoon Killers (1969) and Equinox (1970). Then I'd go record shopping at Frankie's Got It record store, which was owned by "Norfolk sound" purveyor Frank Guida, the Sicilian-American record producer who discovered Gary "U.S." Bonds, Jimmy Soul, Tommy Facenda, and Lenis Guess, and who once received a fan letter from The Beatles. It was at Frankie's that I first became aware of the ouevre of Rudy Ray Moore, Skillet and Leroy, and many others, and bought my first Funkadelic album ("Free Your Mind And Your Ass Will Follow"). I'd peruse my new vinyl treasures while enjoying a chili dog and an Orange Julius as I listened to my waitress boast about her boyfriend's big dick.

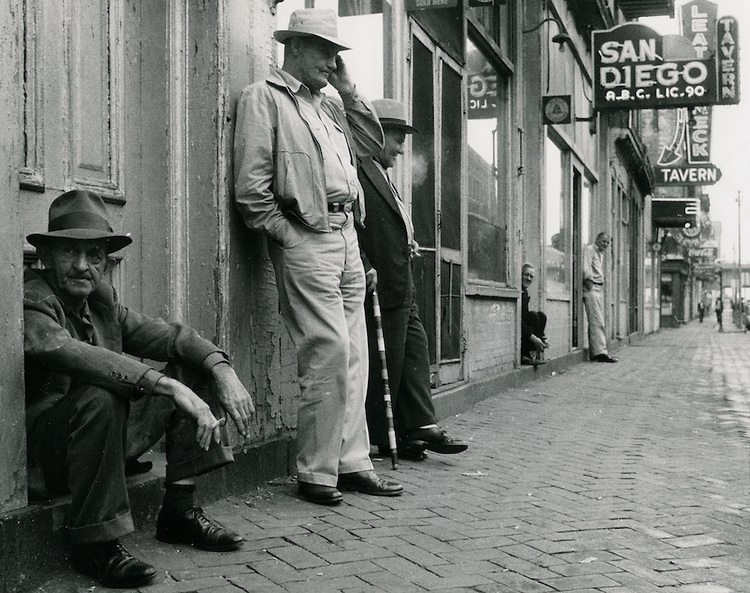

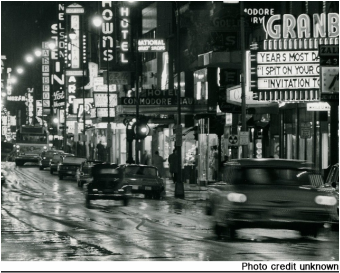

A trip downtown also meant a stop at Henderson's Newsstand, a shabby-looking hole in the wall situated at the junction where the Granby Street of boutiques and department stores gave way to the street of shame so well remembered by generations of sailors who served duty at the Norfolk Naval Station. No less an expert on the subject than Johnny Legend has claimed that Norfolk, Virginia was the sleaziest town he'd ever set foot in. During the late sixties and early seventies, neon-lit taverns and cheap flophouses were still laid out tight as piano keys along this stretch of Granby Street. Hordes of sailors, some from faraway ports, swarmed past derelicts and con men from one bar to the next while MPs prowled the streets for drunk or AWOL gobs.

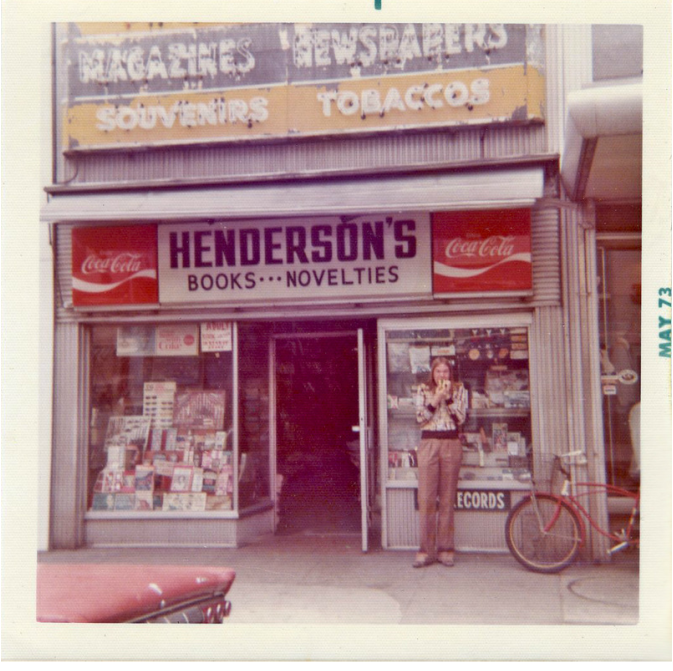

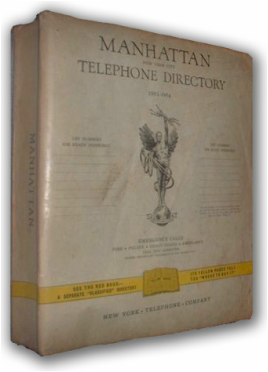

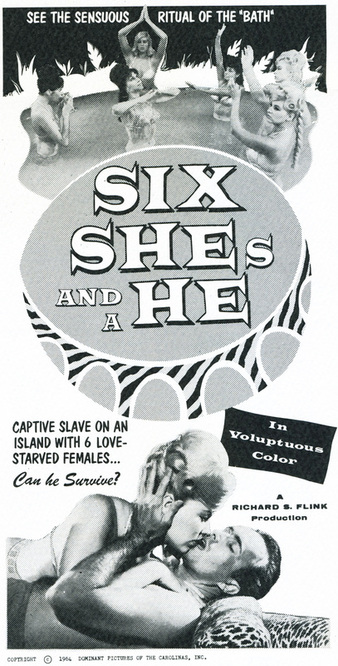

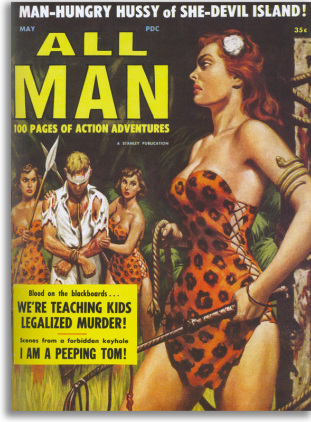

Though it bordered this nether world of gin blossoms and lice, Henderson's Newsstand was, among other things, a respite for the intellectually curious. It was at Henderson's where I first laid eyes on publications such as The Village Voice; Evergreen Review; Ramparts; Ralph Ginsburg's Avant Garde; music zines Creem, Crawdaddy, NME and Melody Maker; the short-lived Eye; and a plethora of underground newspapers such as The East Village Other and The Berkeley Barb. They also sold grayish-colored hot dogs from a rotisserie. It was at Henderson's where I spied a tenth-grade classmate feverishly thumbing through an issue of Iron Man (not the Marvel comic). Most of these titles were not available anywhere else in Norfolk but from Henderson's, which staked its claim within sailor purgatory long before the appearance of head shops and counterculture bookstores.

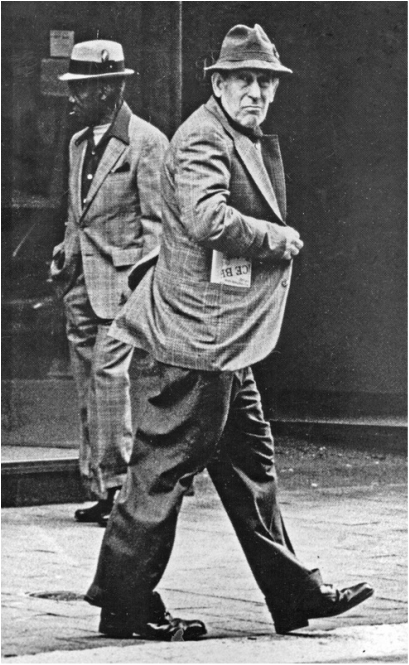

The proprietor of this oasis of literary ephemera was a man named Arthur Goldstein, whom everyone knew as "Bootsie." Diminutive, pallid, and always looking as if he'd just rolled out of bed, Bootsie could be seen evenings at closing time locking the door of his shop and scurrying down Granby Street, the daily racing form protruding from his ill-fitting sports jacket. In his shop, he was unfailingly courteous to anyone who stepped up to his counter to make a purchase or ask about the availability of a publication. But if you happened to catch his eye, you could tell that he was sizing you up. His was a business that depended on him being able to understand his customers.

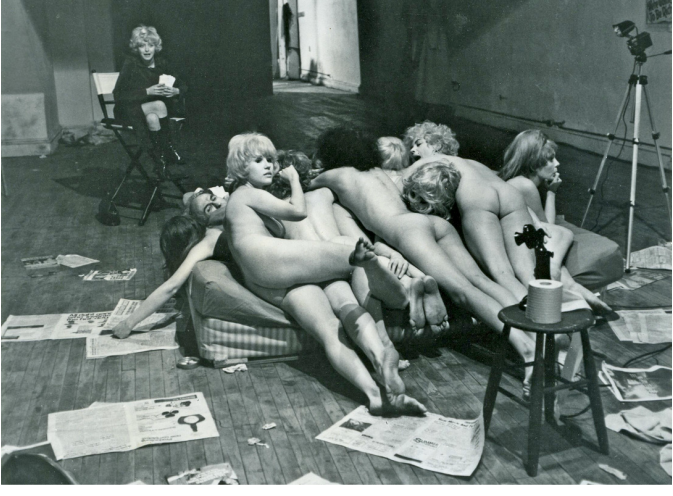

That's because Bootsie was not only the dealer of magazines ranging from Sex to Sexty to After Dark. He also sold, from under the counter, hard core pornography. LOTS of it. Many a sailor returned to his ship with a brown paper bag filled with books and magazines that, at the time, were illegal to either sell or buy. Before 1973's Miller v. California Supreme Court ruling began to loosen legal restrictions against hardcore pornography, a conviction for selling what is easily found nowadays on the internet would likely result in a steep fine and, possibly, a jail sentence. Laws regulating the sale of adult publications varied wildly from state to state, and Virginia's statutes were among the strictest.

Unfortunately for Bootsie, he wasn't always successful in judging the intentions of his customers. Some turned out to be on the payroll of Norfolk's vice squad. During his career, Bootsie was arrested for selling smut a whopping total of 65 times, jailed twice, and fined over $65,000. His first arrest, in 1958 for defying two court orders to rid his store of adult magazines, cost him ten days in jail and $15,000 ( that's $123,000 in today's dollars) plus legal costs. Nevertheless, Bootsie would not back down from city hall's onslaught. He continued to peddle porn to those who wanted it, the law be damned. To genteel Norfolk, he was the problem that refused to go away.

After the wide distribution of Gerard Damiano's Deep Throat (1972) and other explicit films had challenged and changed public attitudes about the acceptability of graphic depictions of sex, Bootsie's little store was still detested but grudgingly tolerated. When a zoning change designed to prohibit new adult bookstores and theaters from opening downtown took effect, Henderson's Newsstand was protected from the ban by a grandfather clause. The years of legal harassment finally seemed to be over for the lantern-jawed smut peddler. But in 1983 Henderson's was one of a half-dozen businesses wiped out by a five-alarm fire. (Along with Henderson's went the Downtown Wig Mart and Mr. Dog-N-Friend.) As staff writer Robert Morris of the Norfolk newspaper, The Virginian Pilot, opined on July 17, "A fire Saturday on Granby Mall may have done something that city officials, judges, and champions of Norfolk's community standards had been unable to do for more than three decades - put Arthur (Bootsie) Goldstein out of business."

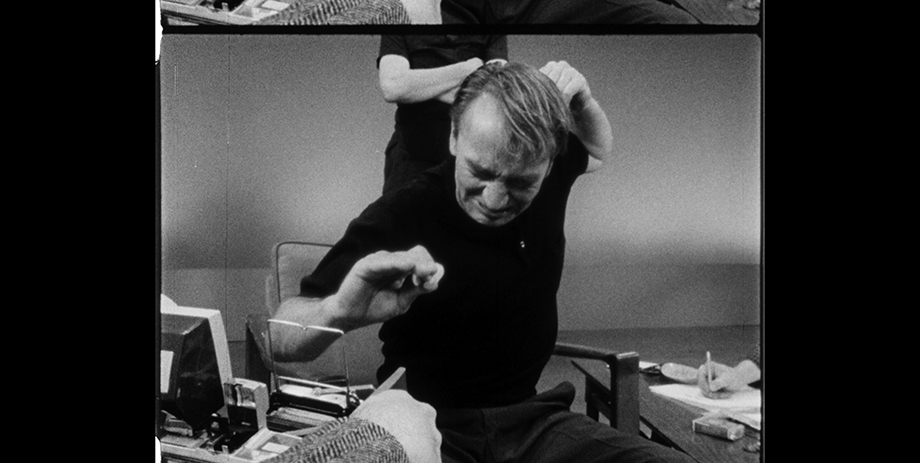

But a fire wasn't about to stop Bootsie. He was quoted the following day in front of his burned-out store: "...we'll get back in there soon...you gotta' work. If you don't work, you die." True to his word, Bootsie opened another store several blocks from the previous location. This newsstand, however, not only lacked the unique character of Henderson's but also no longer had an exemption to sell adult books and magazines. Bootsie was back in the hot seat, spending the next five years repeatedly facing new charges of vending pornography. Each time, his defense was to claim that he hadn't understood the court's orders. In 1988, while covering the most recent dust-up between Bootsie and City Hall, The Virginian Pilot stated: "These photos (one of which appears above) and this report are not the last we'll hear of Bootsie." And it wasn't, though the news took a turn for the tragic.

On June 14, 1989, his 75th birthday, Bootsie was gunned down during a robbery in his newsstand. The frail old man had apparently been trying to escape his killer; the bullets had entered his back and buttocks. Bootsie's murderer, who fled the scene without ever finding the $126,00 bankroll hidden in the store, was never brought to justice. The only suspect in the cold-blooded killing was eventually released for lack of evidence. The sanitized "new" Norfolk proved to be no safer than its seedy forebear, and it was lawlessness, not the law, that finally ended Bootsie's run.

That's because Bootsie was not only the dealer of magazines ranging from Sex to Sexty to After Dark. He also sold, from under the counter, hard core pornography. LOTS of it. Many a sailor returned to his ship with a brown paper bag filled with books and magazines that, at the time, were illegal to either sell or buy. Before 1973's Miller v. California Supreme Court ruling began to loosen legal restrictions against hardcore pornography, a conviction for selling what is easily found nowadays on the internet would likely result in a steep fine and, possibly, a jail sentence. Laws regulating the sale of adult publications varied wildly from state to state, and Virginia's statutes were among the strictest.

Unfortunately for Bootsie, he wasn't always successful in judging the intentions of his customers. Some turned out to be on the payroll of Norfolk's vice squad. During his career, Bootsie was arrested for selling smut a whopping total of 65 times, jailed twice, and fined over $65,000. His first arrest, in 1958 for defying two court orders to rid his store of adult magazines, cost him ten days in jail and $15,000 ( that's $123,000 in today's dollars) plus legal costs. Nevertheless, Bootsie would not back down from city hall's onslaught. He continued to peddle porn to those who wanted it, the law be damned. To genteel Norfolk, he was the problem that refused to go away.

After the wide distribution of Gerard Damiano's Deep Throat (1972) and other explicit films had challenged and changed public attitudes about the acceptability of graphic depictions of sex, Bootsie's little store was still detested but grudgingly tolerated. When a zoning change designed to prohibit new adult bookstores and theaters from opening downtown took effect, Henderson's Newsstand was protected from the ban by a grandfather clause. The years of legal harassment finally seemed to be over for the lantern-jawed smut peddler. But in 1983 Henderson's was one of a half-dozen businesses wiped out by a five-alarm fire. (Along with Henderson's went the Downtown Wig Mart and Mr. Dog-N-Friend.) As staff writer Robert Morris of the Norfolk newspaper, The Virginian Pilot, opined on July 17, "A fire Saturday on Granby Mall may have done something that city officials, judges, and champions of Norfolk's community standards had been unable to do for more than three decades - put Arthur (Bootsie) Goldstein out of business."

But a fire wasn't about to stop Bootsie. He was quoted the following day in front of his burned-out store: "...we'll get back in there soon...you gotta' work. If you don't work, you die." True to his word, Bootsie opened another store several blocks from the previous location. This newsstand, however, not only lacked the unique character of Henderson's but also no longer had an exemption to sell adult books and magazines. Bootsie was back in the hot seat, spending the next five years repeatedly facing new charges of vending pornography. Each time, his defense was to claim that he hadn't understood the court's orders. In 1988, while covering the most recent dust-up between Bootsie and City Hall, The Virginian Pilot stated: "These photos (one of which appears above) and this report are not the last we'll hear of Bootsie." And it wasn't, though the news took a turn for the tragic.

On June 14, 1989, his 75th birthday, Bootsie was gunned down during a robbery in his newsstand. The frail old man had apparently been trying to escape his killer; the bullets had entered his back and buttocks. Bootsie's murderer, who fled the scene without ever finding the $126,00 bankroll hidden in the store, was never brought to justice. The only suspect in the cold-blooded killing was eventually released for lack of evidence. The sanitized "new" Norfolk proved to be no safer than its seedy forebear, and it was lawlessness, not the law, that finally ended Bootsie's run.

One of Bootsie's prior indictments had been for "aiding in the delinquency of a minor." The "delinquency" in question was the act of Bootsie selling airplane glue to a high school student who was assisting the Norfolk Vice Squad in a sting operation. In the sixties, such glue was the drug of choice for wayward teens attracted by its low cost and easy availability. Testor's glue, used by hobbyists to bind the unassembled parts of their plastic Messerschmitts together, had been designated in 1969 by Virginia and other states as a controlled substance. Bootsie was convicted for selling a tube of it to a minor.

This arrest may help explain a peculiar exchange I had with Bootsie in the summer of 1971. A 17-year-old friend had asked me, one year his senior and, therefore, a legal adult, to purchase for him at Henderson's a plastic vibrator (the generic type that would soon be widely available in shopping malls) so he and his girlfriend could, uh, "experiment" at the drive-in theater. I reluctantly agreed, and on carrying out the illicit deed found that Bootsie seemed somewhat reticent about the transaction. After checking my age and making the sale, he suddenly sprang from around the counter, reached up to wrap his arm around my shoulder, and, giving my elbow a paternal pat, rasped these words in my ear: "Whatever you do, make sure that no KIDS get their hands on this!"

This arrest may help explain a peculiar exchange I had with Bootsie in the summer of 1971. A 17-year-old friend had asked me, one year his senior and, therefore, a legal adult, to purchase for him at Henderson's a plastic vibrator (the generic type that would soon be widely available in shopping malls) so he and his girlfriend could, uh, "experiment" at the drive-in theater. I reluctantly agreed, and on carrying out the illicit deed found that Bootsie seemed somewhat reticent about the transaction. After checking my age and making the sale, he suddenly sprang from around the counter, reached up to wrap his arm around my shoulder, and, giving my elbow a paternal pat, rasped these words in my ear: "Whatever you do, make sure that no KIDS get their hands on this!"

Some details for this tribute were drawn from articles written by Robert Morris and Tony Germanotta for The Virginian Pilot. The 1958 photo of downtown Norfolk's skid row is uncredited. Bootsie was photographed by Robie Ray for The Virginian Pilot, and the photo of me eating a hot dog from Henderson's Newsstand was taken by Jim Rosko. This tribute to Bootsie is dedicated to the memory of F. J. Armstrong.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed