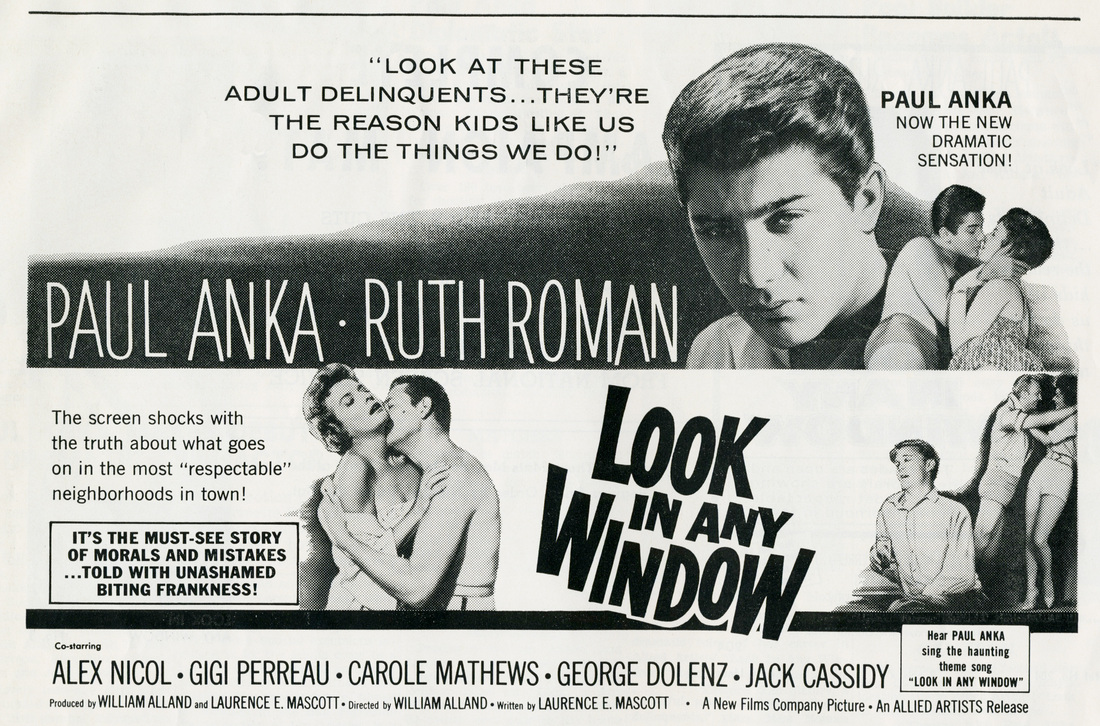

Look In Any Window (1961)

In 1961's Wild in the Country, scripted by leftie playwright Clifford Odets, post-G.I. Elvis Presley starred as a juvenile offender with a violent streak and a gift for writing. That same year, teen idol Paul Anka, for his third feature film, signed on to portray a mopey teenage voyeur who wears a creepy mask and spies on his neighbors. Two pop stars, two disturbed young punks. The verdict: Elvis can't touch Paul Anka's willingness to let go of his star persona in Look In Any Window. Anka's Craig Fowler is one creepy kid.

And suburbia is one swinging scene, baby, as neighbors make time with the spouses next door and throw pool parties that devolve into drunken fistfights. Creepy Craig's father Jay (Alex Nicol) is an under-achieving alcoholic who's been canned from his job, and his mother Jackie (Ruth Roman) is a social climber who favors illicit getaways with playboy-next-door Gareth (Jack Cassidy in his film debut). Gareth's long-suffering wife Betty (Carole Mathews) hides his indiscretions for the sake of daughter Eileen (Gigi Perreau), but Eileen has taken to being impertinent with her elders and dating rude boys who won't come inside to be introduced. And there's that new neighbor Carlo (Robert Dolenz), a widower with broad shoulders which seem tailor-made for Betty to flood with the tears of her frustration.

And suburbia is one swinging scene, baby, as neighbors make time with the spouses next door and throw pool parties that devolve into drunken fistfights. Creepy Craig's father Jay (Alex Nicol) is an under-achieving alcoholic who's been canned from his job, and his mother Jackie (Ruth Roman) is a social climber who favors illicit getaways with playboy-next-door Gareth (Jack Cassidy in his film debut). Gareth's long-suffering wife Betty (Carole Mathews) hides his indiscretions for the sake of daughter Eileen (Gigi Perreau), but Eileen has taken to being impertinent with her elders and dating rude boys who won't come inside to be introduced. And there's that new neighbor Carlo (Robert Dolenz), a widower with broad shoulders which seem tailor-made for Betty to flood with the tears of her frustration.

Remove the cast's stylish clothing, introduce dry humping, and you'd have Sin In The Suburbs (1964), Suburbia Confidential (1966), Suburban Roulette (1968), or nearly any other sixties' sexploitation feature set in a soft porn suburbia where the pool parties and hula contests are a jump-cut away from meetings of secret sock-wearing S&M sex societies and group gropes in the rec room. In writer Laurence E. Mascott's hothouse plunge into suburban fleurs du mal, the sex is always beyond the frame or in cutaway. But it's there: Roman's hot-to-trot housewife abandons a trickling garden hose for the last-minute offer of a high-octane jaunt to Las Vegas with Cassidy's horny hyena; and screams from the victim of an attempted rape summon every neighbor to the scene before the arrival of the girl's mother, who was swooning in the sweaty clutch of the worldly European next door.

Look In Any Window methodically critiques its drunk and cheating grown-ups as the cause of so much teenage angst while tempting the audience with depictions of behavior they've been extended the invitation to consider as socially unacceptable but a pleasure to watch nonetheless. On his decision to star in the film, Anka replied that the film showed "...how troubled marriages affect the kids, shows how lack of attention and care cause wild behavior and that if a child gets love from his parents, he needs nothing else in the world." So Look In Any Window was a prescriptive cold shower for the post-"Chapman Report" world, and all for the benefit of the kids, naturally.

Western vet Alex Nicol and Hitchcock alumnus Ruth Roman head a cast that ratchets up this outré material as if they were auditioning for Edward Albee. Of particular note is Jack Cassidy's licentious lothario, a suburban satyr at play in a manicured Eden, who eagerly steals his every scene. [Popstar alert: Cassidy, a victim of smoking in bed, was the father of seventies' singing star David Cassidy; dialect whiz George Dolenz, who portrays widower Carlo, sired Monkee Mickey.] Anka's own method-y turn as Craig, while seriously overcooked, serves to back up the claim that he chose Look In Any Window because it was a heavier experience than the more frivolous teen films he was being offered. In his autobiography My Way, co-written with David Dalton, Anka admitted that the film was a "...teen movie with higher aspirations." Anka also warbles the lachrymose title song, which could be described as "haunting" even if it weren't from a film about a confused teen pervert.

The only directorial credit of William Alland, a former combat pilot known for producing sci-fi classics The Creature From The Black Lagoon, This Island Earth, and others, the tame Look In Any Window certainly broke no new ground. Sympathetic portrayals of sex offenders had already been seen in films both within and outside the mainstream, such as Richard Hilliard's riskier The Lonely Sex (1959). But Alland's apparently genuine interest in human behavior later led him to produce an award-winning radio show entitled "The Doorway to Life" about the psychology of the brain.

Cinematographer W. Wallace Kelley had previously engineered photographic effects for cold-war sci-fi chillers such as The War Of The Worlds, and later shot many of Jerry Lewis' productions for Hal Wallis. Producer/writer Mascott was a television writer whose credits include an episode of John Cassavettes' Johnny Staccato series. His final feature film foray was Josie's Castle (1972), which featured an orgy with George Takei.

In assigning its protagonist's pathology to parental incompetence and neglect, Look In Any Window echoes Nicholas Ray's superior Rebel Without A Cause (1955). Its depiction of police intransigence anticipates the rebellious teen films of the mid- to late-sixties when attitudes about symbols of authority soured. The abusive methodology of Detective Weber, the angry Sergeant Friday-wannabe intent on bashing a "pervert," loses out to rational and compassionate Detective Lindstrom. It's a "kid gloves" viewpoint that one would expect from purportedly leftist Hollywood. But co-producer and director Alland would seem an odd choice for overseeing such a project. Ten years earlier, tangled in the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings, he had surrendered the names of friends and co-workers, branding them as Communist sympathizers and ensuring that they would not be able to find work.

The Smash Vision DVD of Look In Any Window is transferred from a decent 35mm print loaned from the William Alland estate, and includes two bonuses. The first is the short film The Man Who Pursued Rosebud, exploring Alland's role as a mostly-unseen reporter in Welles' Citizen Kane; and William Alland and H.U.A.C., a painful interview with Alland's second wife Helen, who bitterly cites his collaboration with the HUAC as leading to the end of their marriage.

Look In Any Window methodically critiques its drunk and cheating grown-ups as the cause of so much teenage angst while tempting the audience with depictions of behavior they've been extended the invitation to consider as socially unacceptable but a pleasure to watch nonetheless. On his decision to star in the film, Anka replied that the film showed "...how troubled marriages affect the kids, shows how lack of attention and care cause wild behavior and that if a child gets love from his parents, he needs nothing else in the world." So Look In Any Window was a prescriptive cold shower for the post-"Chapman Report" world, and all for the benefit of the kids, naturally.

Western vet Alex Nicol and Hitchcock alumnus Ruth Roman head a cast that ratchets up this outré material as if they were auditioning for Edward Albee. Of particular note is Jack Cassidy's licentious lothario, a suburban satyr at play in a manicured Eden, who eagerly steals his every scene. [Popstar alert: Cassidy, a victim of smoking in bed, was the father of seventies' singing star David Cassidy; dialect whiz George Dolenz, who portrays widower Carlo, sired Monkee Mickey.] Anka's own method-y turn as Craig, while seriously overcooked, serves to back up the claim that he chose Look In Any Window because it was a heavier experience than the more frivolous teen films he was being offered. In his autobiography My Way, co-written with David Dalton, Anka admitted that the film was a "...teen movie with higher aspirations." Anka also warbles the lachrymose title song, which could be described as "haunting" even if it weren't from a film about a confused teen pervert.

The only directorial credit of William Alland, a former combat pilot known for producing sci-fi classics The Creature From The Black Lagoon, This Island Earth, and others, the tame Look In Any Window certainly broke no new ground. Sympathetic portrayals of sex offenders had already been seen in films both within and outside the mainstream, such as Richard Hilliard's riskier The Lonely Sex (1959). But Alland's apparently genuine interest in human behavior later led him to produce an award-winning radio show entitled "The Doorway to Life" about the psychology of the brain.

Cinematographer W. Wallace Kelley had previously engineered photographic effects for cold-war sci-fi chillers such as The War Of The Worlds, and later shot many of Jerry Lewis' productions for Hal Wallis. Producer/writer Mascott was a television writer whose credits include an episode of John Cassavettes' Johnny Staccato series. His final feature film foray was Josie's Castle (1972), which featured an orgy with George Takei.

In assigning its protagonist's pathology to parental incompetence and neglect, Look In Any Window echoes Nicholas Ray's superior Rebel Without A Cause (1955). Its depiction of police intransigence anticipates the rebellious teen films of the mid- to late-sixties when attitudes about symbols of authority soured. The abusive methodology of Detective Weber, the angry Sergeant Friday-wannabe intent on bashing a "pervert," loses out to rational and compassionate Detective Lindstrom. It's a "kid gloves" viewpoint that one would expect from purportedly leftist Hollywood. But co-producer and director Alland would seem an odd choice for overseeing such a project. Ten years earlier, tangled in the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings, he had surrendered the names of friends and co-workers, branding them as Communist sympathizers and ensuring that they would not be able to find work.

The Smash Vision DVD of Look In Any Window is transferred from a decent 35mm print loaned from the William Alland estate, and includes two bonuses. The first is the short film The Man Who Pursued Rosebud, exploring Alland's role as a mostly-unseen reporter in Welles' Citizen Kane; and William Alland and H.U.A.C., a painful interview with Alland's second wife Helen, who bitterly cites his collaboration with the HUAC as leading to the end of their marriage.