Mondo Pazzo (1963)

Simply put, Mondo Pazzo (aka Mondo Cane 2) is a tough slog. Assembled from segments discarded from Mondo Cane as well as new footage shot by that film's creators, Mondo Pazzo is neither as shocking or as meticulously assembled as its predecessor. Even more damning, many of its revelations this time around appear to be staged or altogether fabricated. As with any "shockumentary" of this era, glimpses of the pre-internet world, when most viewers would have lacked the means to experience other cultures first-hand, are initially as fascinating as thumbing through photo albums from childhood. But interest soon turns to boredom, as Mondo Pazzo, lacking the contextual charge of its predecessor, shuffles from one tired segment to another.

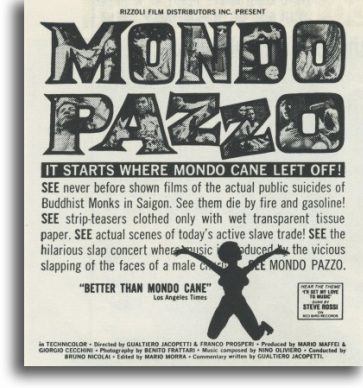

Years later, the filmmakers would disown the film, claiming that they were enticed by Rizzoli Film Distributors to create a money-making sequel to their initial hit. One cannot help but suspect that their disavowal of Mondo Pazzo may also be based on the film's heavy ratio of faked footage. The advertising campaign stressed "never before shown" footage of the immolation of "Buddhist monks in Saigon" (in actuality, just one monk). Gualtiero Jacopetti, one of the film's co-creators, has since admitted that this footage was faked using a mannequin created by uncredited special effects artist Carlo Rambaldi (E.T.'s daddy!).

The narration, written by Jacopetti, is at its most "cutting" in the film's introductory sequence, which takes the U.K. censors to task for hypocrisy in trimming Mondo Cane's depiction of dogs as cuisine while tolerating canine vivisection in laboratories hidden from public view. From there, it's mostly a faded carbon-copy of Mondo Cane, as successive segments mirror those from the original film.

The Yves Klein segment from Mondo Cane is replaced by a profile of "stomatal painter" Achilles Gropulus, whose scantily-clad assistants spit colored paint onto a canvas while a toga-clad chorus gargles noisily. Elsewhere, a German painter named Horst Sonnering, clad in a minotaur costume that wouldn't pass muster in a low-budget peplum film, attacks his canvas within a circle of fire to attain the correct mood for his artworks based on Dante's Inferno. Sadly, these scenes do little but reinforce the anti-intellectual notion that artists are eccentric kooks best viewed with caution.

The narration, written by Jacopetti, is at its most "cutting" in the film's introductory sequence, which takes the U.K. censors to task for hypocrisy in trimming Mondo Cane's depiction of dogs as cuisine while tolerating canine vivisection in laboratories hidden from public view. From there, it's mostly a faded carbon-copy of Mondo Cane, as successive segments mirror those from the original film.

The Yves Klein segment from Mondo Cane is replaced by a profile of "stomatal painter" Achilles Gropulus, whose scantily-clad assistants spit colored paint onto a canvas while a toga-clad chorus gargles noisily. Elsewhere, a German painter named Horst Sonnering, clad in a minotaur costume that wouldn't pass muster in a low-budget peplum film, attacks his canvas within a circle of fire to attain the correct mood for his artworks based on Dante's Inferno. Sadly, these scenes do little but reinforce the anti-intellectual notion that artists are eccentric kooks best viewed with caution.

Lovers of marzipan may salivate over footage from the Mexican Day of the Dead celebration: life-size, edible human corpse replicas, complete with internal organs, are greedily devoured by hordes of happy muchachos. Bugs are again devoured, this time not by New York socialites but by working-class Mexican revelers who gorge themselves on tortillas filled with hot sauce and living insects, pausing only to wipe bits of spicy black thorax and mandible from their faces. Luckier insects are bejeweled and worn as ornaments, purportedly in the Mexican world of high fashion. That's doubtful, but this segment may be the inspiration for a titillating episode in Pasquale Festa Campinile's 1968 La Matriarca (aka "The Libertine").

These and other segments not only lack the punch of the previous work, but follow one another haphazardly. For most of its running time Mondo Pazzo chugs along as if it were a bad example of reality television, its latter-day successor, managing to shock the viewer from bored complacency only sporadically. A recital of piano music accentuated by a conductor slapping the faces of a line of tuxedoed men recalls Moe, Larry and Curly until one notices the blood streaming from the mens' nostrils. A segment depicting the arrest of slavers, their child victims deformed by being forced to wear shackles designed to twist their limbs and render them crippled, deeply disturbs regardless of its veracity. One hopes that it is staged. But the majority of Mondo Pazzo is merely a tired retread of the first film, and is recommended only to genre completists, bless their hearts, or fans of singing group The Four Preps, crooners of the title theme.

Whatever the flaws of Mondo Pazzo, Blue Underground cannot be faulted for their pristine transfer to DVD (under the alternate title Mondo Cane 2) from the film's original negative. Those who remember the faded Vidmark VHS will be surprised to see the vibrant colors of this fifty-year-old film.

Whatever the flaws of Mondo Pazzo, Blue Underground cannot be faulted for their pristine transfer to DVD (under the alternate title Mondo Cane 2) from the film's original negative. Those who remember the faded Vidmark VHS will be surprised to see the vibrant colors of this fifty-year-old film.

[This review previously appeared, in different form, in ecco, the world of bizarre video, Volume One, Number One.]