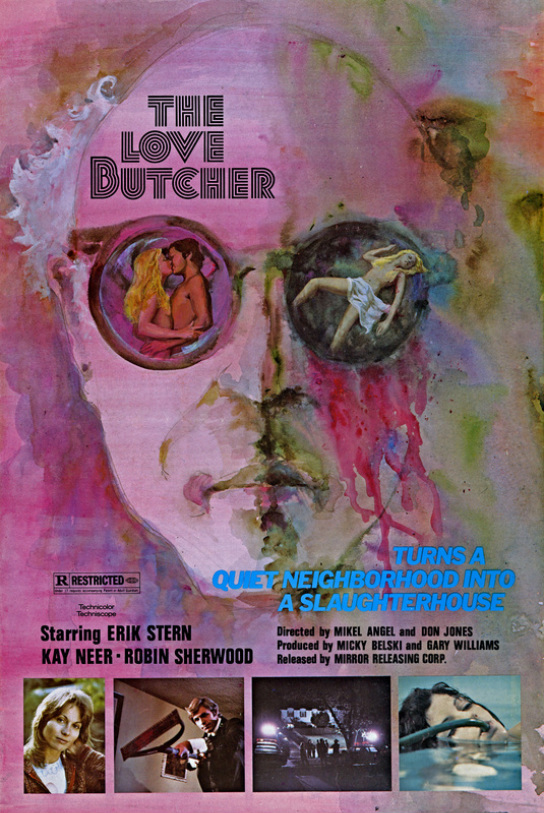

The Love Butcher (1975)

Mikel Angel and Don Jones' schlocky The Love Butcher showcases an exuberantly realized performance by Erik Stern as a misogynistic miscreant with a dual personality. As Caleb, Stern is a bespectacled, bald-headed gardener, a self-described "gimp" whose ineptitude and pathetic demeanor draws the wrath of the suburban Los Angeles matrons for whom he labors. Once he suffers their abuse, however, Caleb's alter-ego Lester, a debonair ladykiller, arrives on the scene to first seduce and then slaughter those who have slighted his "brother." Scenes of Lester menacing his victims are sandwiched between hateful, Milligan-esque domestic encounters, resulting in a tongue-in-cheek, sociopathic soap opera.

Though the film has been criticized for not delivering sufficient gore to warrant the promise of its title, the opening segment demonstrates that The Love Butcher blithely ignores any standards established by its peers. A slow pan through a well-manicured suburban garden reveals a woman's body run through with a pitchfork. The credits roll as the camera incongruously lingers on colorful close-ups of roses, birds of paradise, and other beauteous blossoms. Meanwhile, a florid soundtrack seemingly lifted from a Herbert Ross film flows sweetly in the background.

As if the script were written by the bumbling Caleb, The Love Butcher revels in defying usual storytelling logic. Although the murders are committed using various gardening implements, no one suspects the creepy gardener who works for ALL of the victims. At the scene of a killing, gruff Lieutenant Don Stark (Richard Kennedy) observes that "...from the outside, (the killer) could be...very ordinary." Cut to Caleb, who - with his Coke-bottle-thick glasses and yellowed buck teeth - is so freaky-geeky that he'd stand out from the crowd at a comic book convention.

A deliberate mash-up of black humor and seventies-era bad taste, The Love Butcher doesn't disappoint. Scenes of the simpering Caleb undergoing humiliating lectures from his evil twin (a toupée perched atop a chair) are both ridiculous and oddly unnerving. Also deserving mention is the method used by Lester to gain entry to his victims' homes, which involves the wearing of costumes barely more subtle than those popularized by the Village People. Most risible is his turn as a Puerto Rican door-to-door record salesman. This use of disguises was perhaps inspired by Jack Smight's dark comedy No Way To Treat A Lady (1968), which starred Rod Steiger as a Broadway producer turned serial killer who uses impersonations to gain entry to the homes of middle-aged women; and a late revelation recalls the genesis of the sibling rivalry in Robert Aldrich's grotesque gothic What Ever Happened To Baby Jane? (1962).

Though the female victims are broadly etched stereotypes tending towards the cruel and promiscuous, Mikel Angel and James Tanenbaum's misanthropic script savagely slanders both genders. From the cranky businessman (Louis Ojena, the mummy from Orgy of the Dead) who badgers his wife (Robin Sherwood of Tourist Trap) about her clock radio to the whiny, ineffectual newspaper reporter Russell (Jeremiah Beecher), who's more Jimmy Olsen than Carl Bernstein, the male caricatures are as unsympathetic as their feminine counterparts. This lack of nuance creates a welcome distancing effect, enabling the viewer to accept The Love Butcher at least most of the time as a dark comedy. But when Lester focuses his murderous impulses on the film's most kindly female character, his modus operandi dissolves along with viewer detachment.

In a supplemental commentary track, cinematographer Don Jones reveals that first- (and only-) time director Angel walked away from The Love Butcher prior to its completion. Jones, who had previously directed the cinema maudit Schoolgirls in Chains (1973), subsequently finished the film, which may explain the abrupt shifts in tone from laughable lampoonery to earnest thriller. Jones recalls, for example, that one of the most inspired bits of derangement, in which Lester's failed seduction of one victim leads him to "compose" a fantasy of success as he mimics an orchestra conductor, was added to the film after Angel's departure. Several other scenes identified by Jones as his handiwork successfully generate the tension expected from a suspense feature, whereas Angel seems more interested in Stern's skill at impersonating character types. The result of two disparate visions, the film's schizophrenia oddly mirrors its title character's dueling personalities.

Code Red's 2.35:1 widescreen DVD of The Love Butcher is a major improvement over the pan and scanned videotape previously available from Monterey Home Video, though the print itself is short of pristine. Aside from the commentary track, there are no extras.

As if the script were written by the bumbling Caleb, The Love Butcher revels in defying usual storytelling logic. Although the murders are committed using various gardening implements, no one suspects the creepy gardener who works for ALL of the victims. At the scene of a killing, gruff Lieutenant Don Stark (Richard Kennedy) observes that "...from the outside, (the killer) could be...very ordinary." Cut to Caleb, who - with his Coke-bottle-thick glasses and yellowed buck teeth - is so freaky-geeky that he'd stand out from the crowd at a comic book convention.

A deliberate mash-up of black humor and seventies-era bad taste, The Love Butcher doesn't disappoint. Scenes of the simpering Caleb undergoing humiliating lectures from his evil twin (a toupée perched atop a chair) are both ridiculous and oddly unnerving. Also deserving mention is the method used by Lester to gain entry to his victims' homes, which involves the wearing of costumes barely more subtle than those popularized by the Village People. Most risible is his turn as a Puerto Rican door-to-door record salesman. This use of disguises was perhaps inspired by Jack Smight's dark comedy No Way To Treat A Lady (1968), which starred Rod Steiger as a Broadway producer turned serial killer who uses impersonations to gain entry to the homes of middle-aged women; and a late revelation recalls the genesis of the sibling rivalry in Robert Aldrich's grotesque gothic What Ever Happened To Baby Jane? (1962).

Though the female victims are broadly etched stereotypes tending towards the cruel and promiscuous, Mikel Angel and James Tanenbaum's misanthropic script savagely slanders both genders. From the cranky businessman (Louis Ojena, the mummy from Orgy of the Dead) who badgers his wife (Robin Sherwood of Tourist Trap) about her clock radio to the whiny, ineffectual newspaper reporter Russell (Jeremiah Beecher), who's more Jimmy Olsen than Carl Bernstein, the male caricatures are as unsympathetic as their feminine counterparts. This lack of nuance creates a welcome distancing effect, enabling the viewer to accept The Love Butcher at least most of the time as a dark comedy. But when Lester focuses his murderous impulses on the film's most kindly female character, his modus operandi dissolves along with viewer detachment.

In a supplemental commentary track, cinematographer Don Jones reveals that first- (and only-) time director Angel walked away from The Love Butcher prior to its completion. Jones, who had previously directed the cinema maudit Schoolgirls in Chains (1973), subsequently finished the film, which may explain the abrupt shifts in tone from laughable lampoonery to earnest thriller. Jones recalls, for example, that one of the most inspired bits of derangement, in which Lester's failed seduction of one victim leads him to "compose" a fantasy of success as he mimics an orchestra conductor, was added to the film after Angel's departure. Several other scenes identified by Jones as his handiwork successfully generate the tension expected from a suspense feature, whereas Angel seems more interested in Stern's skill at impersonating character types. The result of two disparate visions, the film's schizophrenia oddly mirrors its title character's dueling personalities.

Code Red's 2.35:1 widescreen DVD of The Love Butcher is a major improvement over the pan and scanned videotape previously available from Monterey Home Video, though the print itself is short of pristine. Aside from the commentary track, there are no extras.

[This review originally appeared, in different form, in ecco, the world of bizarre video, Volume One, Number Three.]