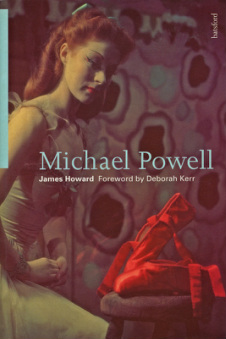

In his 1996 book Michael Powell (Batsford), author James Howard reveals through recollections of the filmmaker's associates that the directorial half of "The Archers" was not an especially pleasant boss. In fact, some who worked with him have claimed that Powell seemed to have a sadistic streak, sometimes reducing actors to tears if their performance didn't please him.

Although dancer Moira Shearer, the star of Powell's classic The Red Shoes, found him to be "a director of great cinematic invention and originality," she also observed that "he neither understood nor respected actors and, far from creating a sympathetic atmosphere in the studio, he created the reverse. It was a damaging experience for many people."

The late, great cameraman Jack Cardiff (1947's Black Narcissus, among many others) termed Powell's directorial style as "very abrasive," and recalled that he would be intentionally rude to lesser-known actors. "You're not very good, are you? Who's your agent?" are examples of Powell's attacks cited by Cardiff, who observes that the director "...believed this sort of insult would prick them into a better performance, but I don't think it ever did."

Tyrannical filmmakers are a staple of the film industry, as anyone who has watched the YouTube clip in which director David O. Russell verbally - and almost physically - assaults Lily Tomlin (whose own tirades are legendary) on the set of I Heart Huckabees (2004) will attest. Perhaps whenever perfectionist artistes must entrust their vision to interpretation by others, frayed nerves and rising tempers are an inevitable byproduct of the creative process. Joseph von Sternberg, John Ford (who purportedly made John Wayne cry!), and Kurosawa Akira are only three examples of filmmakers known for their imperious behavior toward actors and crew members.

Conversely, something markedly different occurred when a former co-worker of mine, an amateur actor who occasionally appeared in television commercials and off-Broadway stage productions, was given a non-speaking role in John Waters' Serial Mom (1994). This part-time actor fondly recalled that the Baltimore filmmaker was the kindest, most considerate professional he had ever worked with. Although his part in the film was ultimately cut to mere seconds of screen time, my co-worker and the other members of the cast and crew received a personally written thank-you note from Waters and an invitation to the premiere.

Life is indeed full of wonder when the self-professed "Prince of Puke," whose once-transgressive films reveled in eye-gouging, feces-eating mayhem posts thank-you cards to the least significant members of his cast, but the proper British director behind such sensitive character studies as I Know Where I'm Going (1945) frequently bestowed on his actors the aural equivalent of a shoebox full of dog shit.

The late, great cameraman Jack Cardiff (1947's Black Narcissus, among many others) termed Powell's directorial style as "very abrasive," and recalled that he would be intentionally rude to lesser-known actors. "You're not very good, are you? Who's your agent?" are examples of Powell's attacks cited by Cardiff, who observes that the director "...believed this sort of insult would prick them into a better performance, but I don't think it ever did."

Tyrannical filmmakers are a staple of the film industry, as anyone who has watched the YouTube clip in which director David O. Russell verbally - and almost physically - assaults Lily Tomlin (whose own tirades are legendary) on the set of I Heart Huckabees (2004) will attest. Perhaps whenever perfectionist artistes must entrust their vision to interpretation by others, frayed nerves and rising tempers are an inevitable byproduct of the creative process. Joseph von Sternberg, John Ford (who purportedly made John Wayne cry!), and Kurosawa Akira are only three examples of filmmakers known for their imperious behavior toward actors and crew members.

Conversely, something markedly different occurred when a former co-worker of mine, an amateur actor who occasionally appeared in television commercials and off-Broadway stage productions, was given a non-speaking role in John Waters' Serial Mom (1994). This part-time actor fondly recalled that the Baltimore filmmaker was the kindest, most considerate professional he had ever worked with. Although his part in the film was ultimately cut to mere seconds of screen time, my co-worker and the other members of the cast and crew received a personally written thank-you note from Waters and an invitation to the premiere.

Life is indeed full of wonder when the self-professed "Prince of Puke," whose once-transgressive films reveled in eye-gouging, feces-eating mayhem posts thank-you cards to the least significant members of his cast, but the proper British director behind such sensitive character studies as I Know Where I'm Going (1945) frequently bestowed on his actors the aural equivalent of a shoebox full of dog shit.

New this installment are reviews of William Castle's It's A Small World (1950) and Georges Franju's Le téte contre les murs (1958). Added to the archive is Joe D'Amato's Eva nera (aka Black Cobra, 1976).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed